Construction began in 1897 on what was then known as the Gare D’Orsay ahead of the 1900 World’s Fair. It would not be until a century later that the building took on the role of the museum. The Orléans Railway Company felt that Gare Austerlitz lacked centrality and would hamper the onslaught of visitors for the World’s Fair. D’Orsay is located a stone’s throw from the Louvre and Légion d’honneur, the building needed to reflect the district’s highly decorated, historical nature. Architect Victor Laloux won the bid to create the train station and accompanying hotel due to the success of his previous project, the Hôtel de Ville in Tours. He made a Beaux-Arts gem replete with elegant arches and coffered ceilings that has withstood changing fashions and the test of time. Gare D’Orsay was threatened by destruction many times but endured. It served many purposes in addition to the intended purpose of a train station, including a central location for prisoner of war administration during WWII, a grandstand for political announcements. It was here that Charles de Gaulle announced his re-entry into politics, and even a movie set, including the Orson Welles production of Kafka’s The Trial. Today, the Gare D’Orsay houses a museum of modern art. What ties all these seemingly disparate uses together? The concept of liminality.

liminal (adj.),

Relating to a transitional or initial stage of the process.

Occupying a position at, or on both sides of, a boundary or threshold.

Oxford English Dictionary via Lexico.com

- The Gare D’Orsay is a Liminal Space

This article about art would be remiss if it did not call to attention the nature of the Gare D’Orsay as a liminal space. The art-inclined over usage of this concept, but it rings true in this circumstance. Sometimes these spaces can be fraught or even scary to an individual experiencing one. Think middle school—there is lots of change about to happen there, but no 11-year-old can be entirely sure what this change will mean. It feels like a long dark hallway with unknown contents within. A train station is also an ideal example because it is neither home nor the destination the traveler intends to reach. Anyone who has waited for a train or airplane can explain the unique discomfort of existing in liminal space. No one can blame you for a 7 am dirty martini or a shopping bag filled with duty-free cigarettes and snow globes. At least not waiting at Penn Station or Logan Airport. Being neither here nor there is decentering. Liminal spaces in Gare D’Orsay carried through this concept of discomfort in the many iterations the D’Orsay experienced within its lifetime.

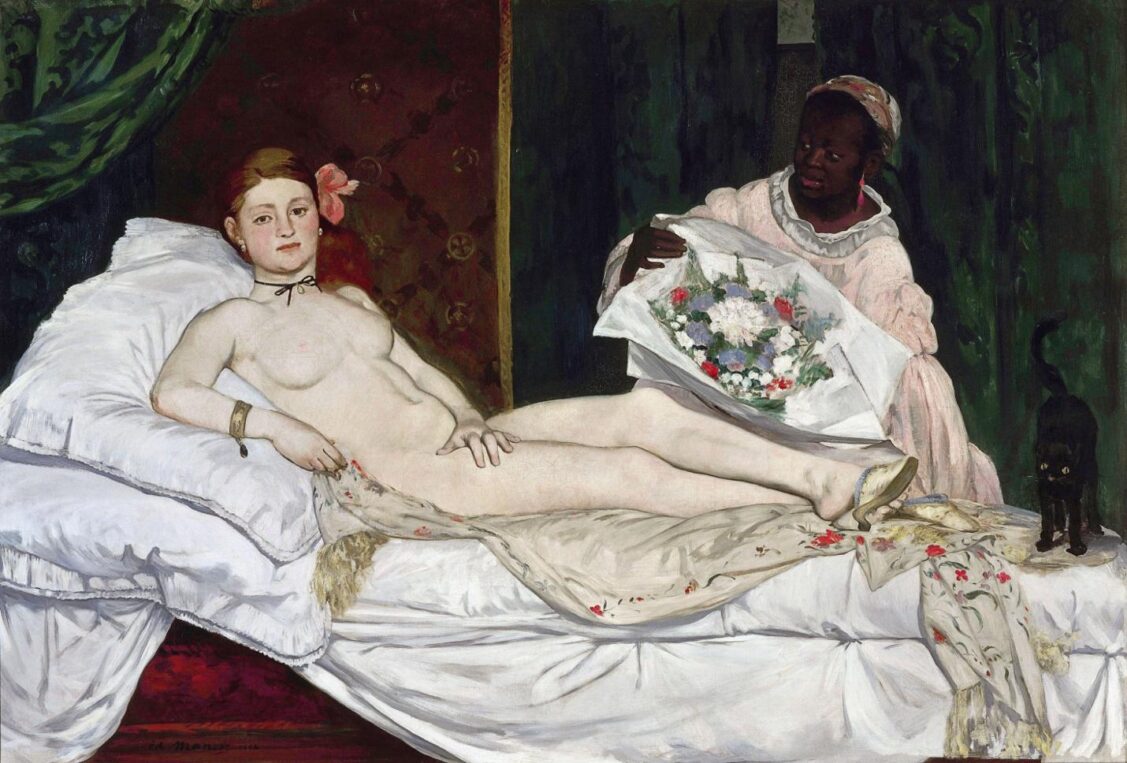

aEdouard Manet, Olympia, 1863 via Google Art Project

In the wartime iteration, the D’Orsay was an office for sending packages to prisoners of war. These men were neither home safe nor were they dead or even on the front lines. They existed in a spooky, uniquely dangerous in-between space. Charles de Gaulle also used it to announce his re-entry into politics, which he returned to after retiring nearly 20 years earlier. In that space, De Gaulle was both a former and current politician all at once. Even during its turn on the big screen in The Trial, protagonist Josef K. occupies a unique place between innocence and guilt that is eerie to embody. And finally, in the current iteration, the Musée D’Orsay, places a flag squarely between modern art and the historical past. It houses images like Edouard Manet’s Olympia, an all too real example of the odalisque. Typically, an odalisque is a celebration of the female form and goddess-like sexuality. The woman depicted in Olympia is coarsely sexual and perhaps too young for her occupation. She is very self-aware, almost sizing up the viewer. She is not a fictional concept of a woman but a young woman selling her body. It looks like art but certainly does not feel like it without the distance history painting offered.

- It’s so meta! Famous Train Paintings are in the Museum

Edouard Manet famously debuted his train paintings in 1874 to much ridicule. Trains were fascinating and of-the-moment pieces of technology that brought on cultural changes. It was only natural for artists in the zeitgeist to be interested in the life-changing locomotives. However, it was Claude Monet that took this concept and ran with it. He was at the forefront of the Impressionist movement and sought to capture an impression of reality within the moment he was experiencing. It was an embodied practice that required Plein-aire practices. Monet asked the leadership of Gare Saint-Lazare for permission to paint Plein-aire inside their station. Saint-Lazare still operates today and is one of Paris’ busiest train stations. It served the Northwest of France, with a terminus in Normandy. It was known as the Paris-La Havre line, an area that would serve as a front for the first world war less than 40 years later.

Claude Monet, Gare Saint-Lazare, 1877 via Wikipedia

The paintings, one of which is still a part of the D’Orsay collection, captures the moment a train pulls up to the platform. It conveys the rush of heat and steam an observer feels when the powerful machine screeches to what seems like an impossible stop. Even today, it is a heart-racing experience when teamed with the expectation of travel and the destabilization of the liminal space. Harvard College also has a Monet train in their collection for viewers wishing to capture the magic without utilizing their passports. The moment frozen in time can also be enjoyed at home with a giclee print and with a set of nice picture lights that are fit to the decor.

- Gare D’Orsay Almost Didn’t Become a Museum.

The Musée D’Orsay was a museum that almost was not. The train lines built for the 1900 World’s Fair became obsolete as other lines expanded. On January 1, 1973, the Hôtel D’Orsay permanently shuttered its doors. There were discussions of rebuilding a modern hotel, but poor foot traffic thwarted nearby efforts to do the same. By 1978, the French Government undertook a commission regarding the formation of a museum. It was restored by Italian designer Gae Auletni. The 1970s showed increased interest in artists from the second half of the 19th century. Although perhaps people identified with a time of change, the 1960s and 1970s were largely unstable as the post-war world took shape. In 1977, Gare D’Orsay became a historical monument. It would not be until December 1, 1986, that President François Mitterand would open doors to the Museum beloved today.

bMusee D’Orsay via wikipedia, photograph by Benh

Walking through the long aisles of the Musée D’Orsay, it is easy to imagine it as a train station. Despite long appearances in a museum setting. Gare D’Orsay became defunct due to short platforms that didn’t allow for modern electric trains. The original clock remains a key architectural feature in the Museum. The structure makes sense in its original context, which may not be far from the current iteration, after all. Late 19th art shows marked difference that is neither historically linked nor as visionary as the abstraction of the 1950s and 1960s. The Museum feels like it has always been there because, in a sense, it always has. The liminal space has always been there, and it has only been the vessel that changed. What was once a container for train travel is now a vessel for intellectual journies. As much as the D’Orsay changes, the more it stays the same.

Works Cited

French Ministry of Culture. 2021. Musee D’Orsay History. Accessed June 30, 2021. https://www.musee-orsay.fr/en.

Martin, Samantha De. 2020. An Italian in Paris–When Gae Aulenti Restored the Musee d’Orsay. Accessed June 29, 2021. https://www.bulgarihotels.com/en_US/milan/whats-on/article/milan/in-the-city/an-italian-in-paris—when-gae-aulenti-restored-th.

Wikipedia. 2021. Gare d’Orsay. March 11. Accessed June 29, 2021. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gare_d%27Orsay.

—. 2021. Gare Saint-Lazare. March 2021. Accessed June 29, 2021. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gare_Saint-Lazare_(Monet_series).